SOME PROGRESS BUT QUESTIONS REMAIN

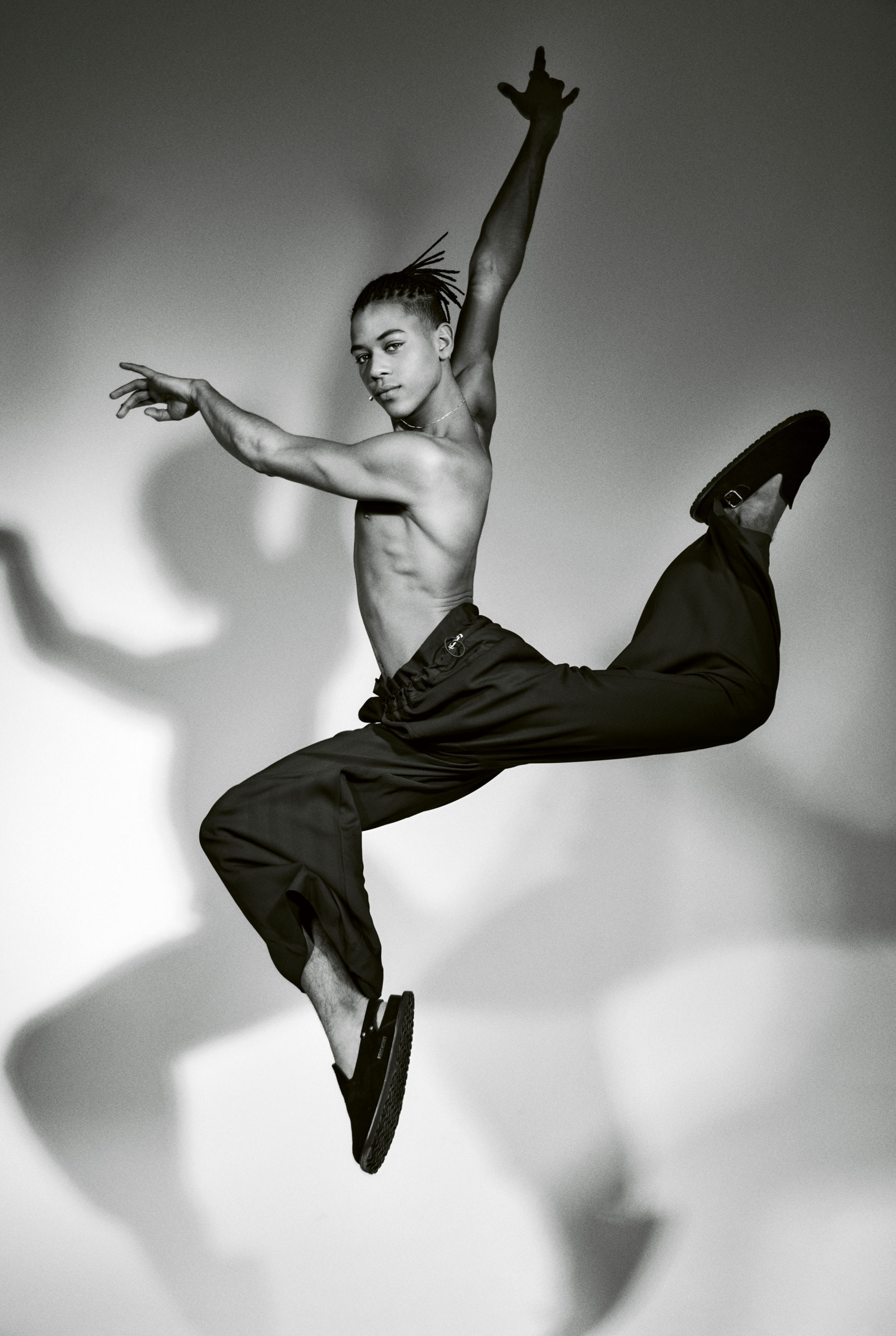

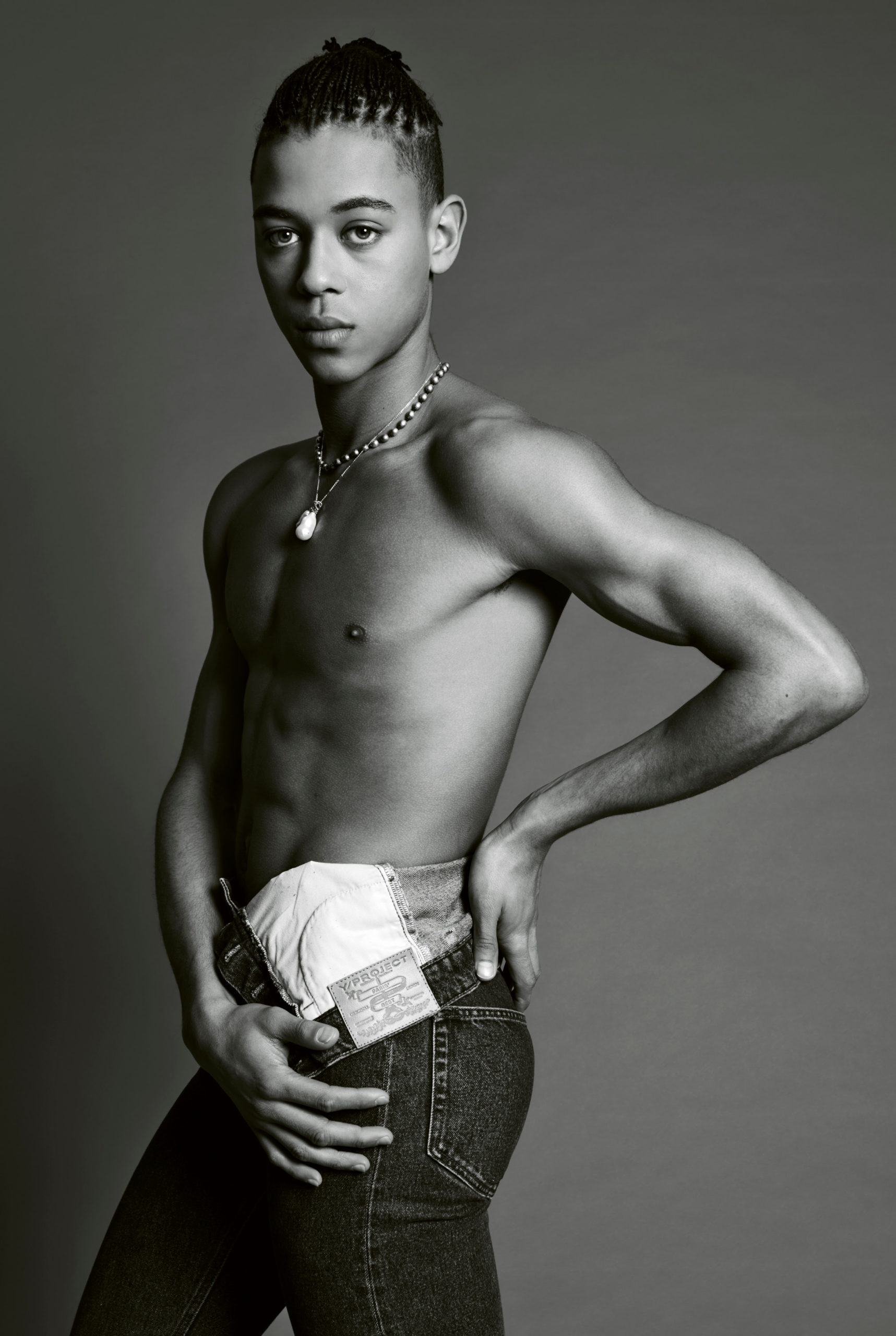

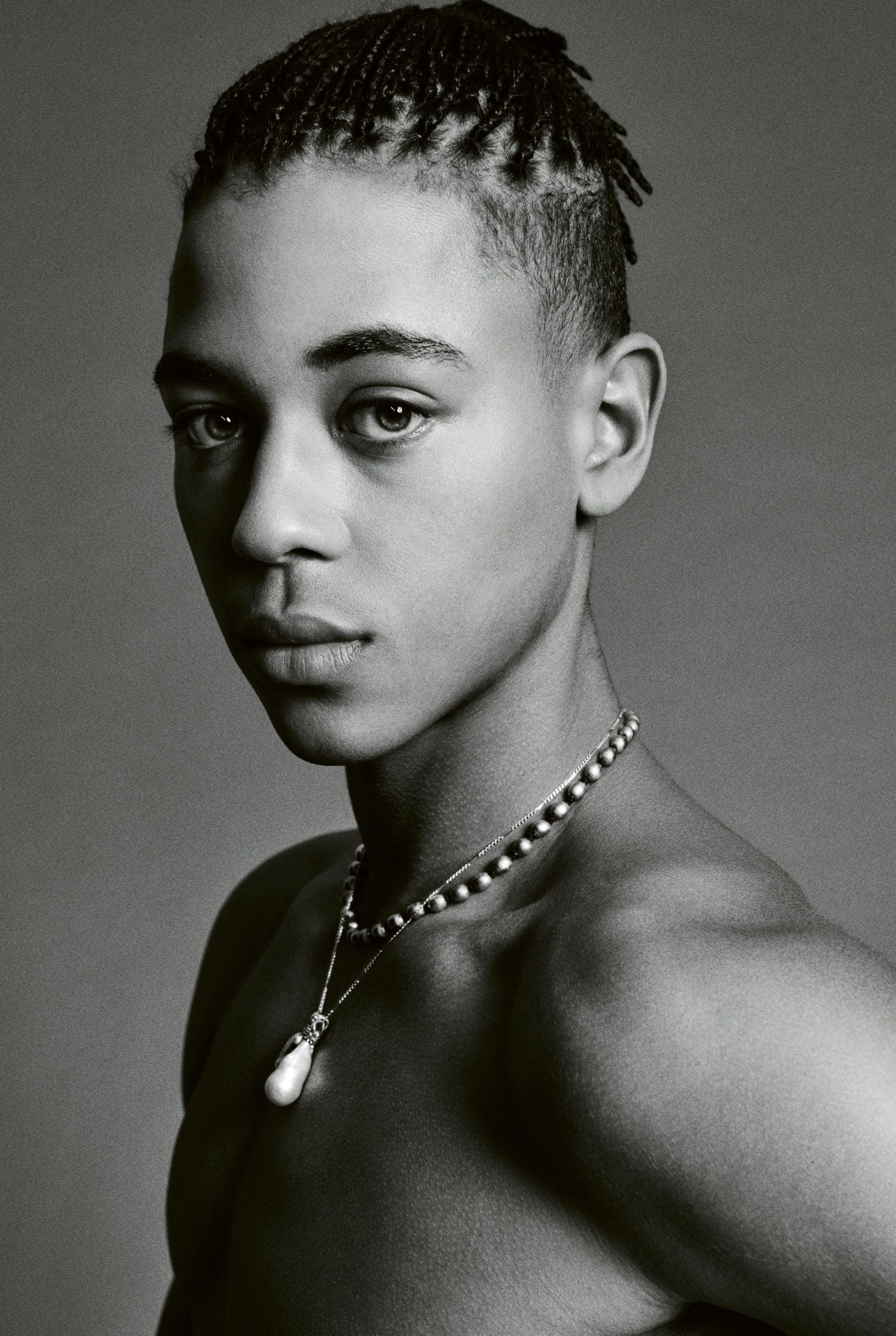

A year and a half later, the dancer believes the atmosphere within the institution has changed. « Beyond the number of signatures, I think that everyone has thought about these questions. And ultimately, our aim was for people to at least take the time to reflect on these questions and engage in discussions around the issue. I think a lot of them didn’t necessarily think about it, and the simple fact we talked about it helped them to realise certain things, what is acceptable and what’s not, and also how we, the ones it affects directly, deal with this situation. » First attempted by Benjamin Millepied, director of dance at the Paris Opera from 2014 to 2016 – who wanted to implement more diversity within the ballet, but was met with the argument that having non-whites dance would be « a distraction » – the process of transformation was this time enabled by Aurélie Dupont, the étoile who succeeded him in that position, and Alexander Neef, director of the Opera since September 1st 2020. Described by Guillaume Diop as “a benevolent, hyper-understanding and attentive interlocutor”, he presented at a press conference in February 2021 the conclusions of the report on diversity within the institution, commissioned in the wake of the manifesto from historian Pap Ndiaye and Secretary general of the Human Rights Commissioner, Constance Rivière. The result? « The end of the highly questionable practice of blackface and make-up for stereotypical roles in all productions », the adaptation of « work tools, such as make-up and clothing, to different skin colours », « the contextualisation » of certain works, and an effort to broaden the recruitment process for the Opera’s artists, and in so doing to diversify the audience – the idea being that, by seeing themselves represented on stage, children from a wider range of backgrounds could become interested in classical dance.

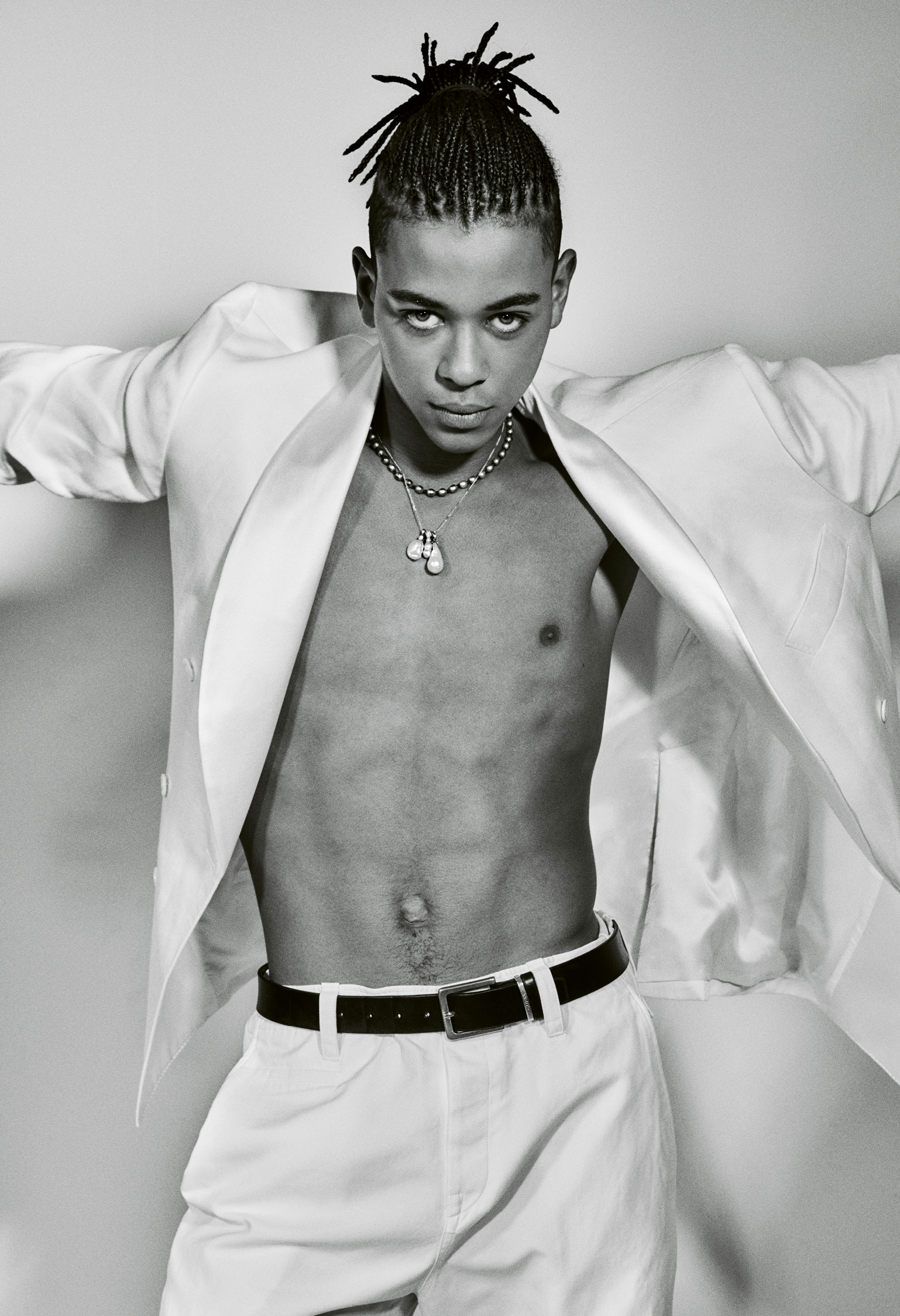

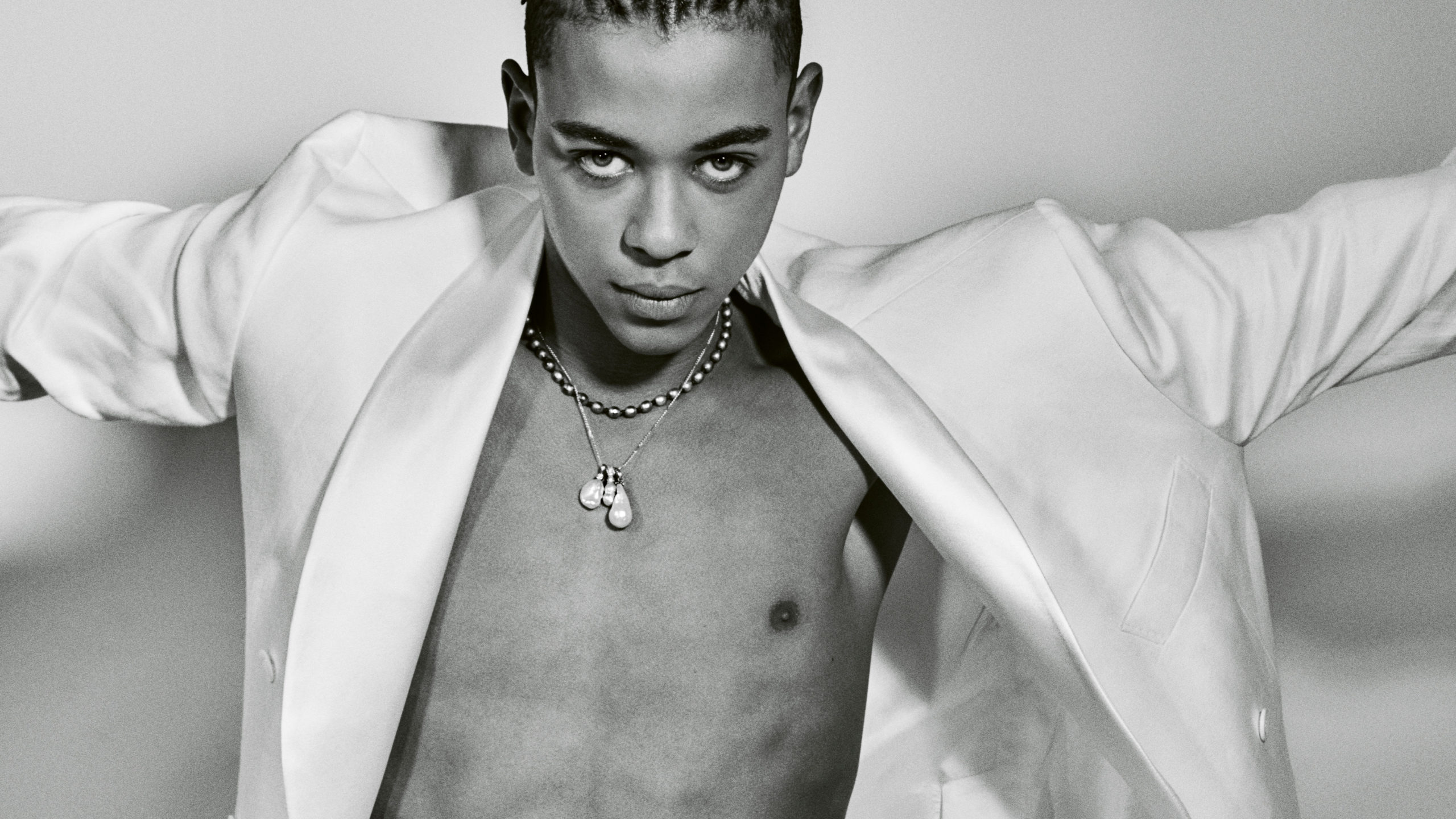

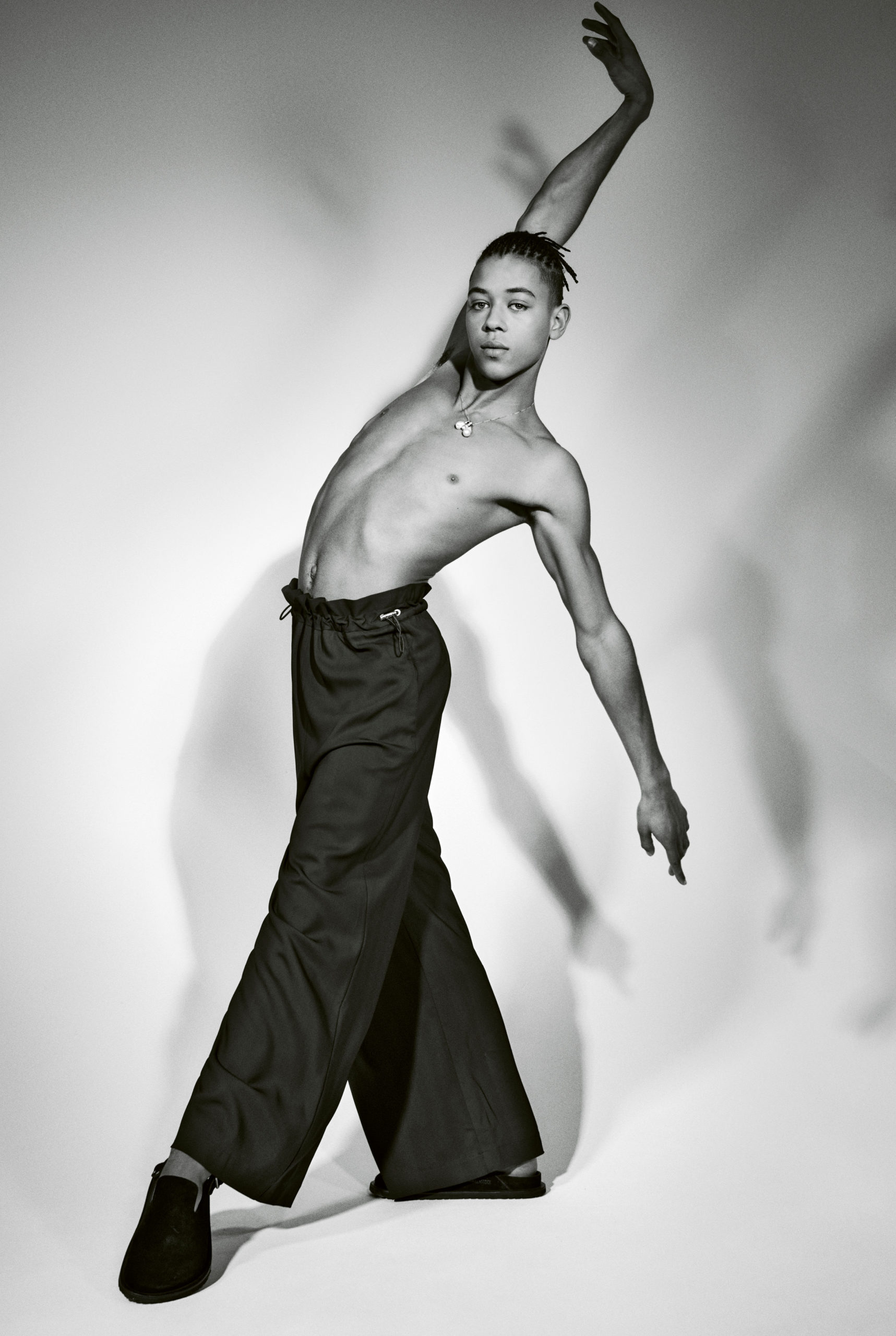

When asked if such an evolution makes him fear that his dancing skills, charisma and joie de vivre on stage will be put forward only as a symbolic effort to seem inclusive, Guillaume Diop replies frankly: « When I talk to other POC, this is what often comes up: sometimes when we don’t get something, it’s because of our skin colour; and when we do get something, we tend to think it’s also because of our skin colour. It scares me a little bit, I think about it, and I know a lot of people also think it’s the reason why it’s happening to me, which is quite complicated to deal with. But to reassure myself, I try to focus on the fact that I work very hard, and that if I have what I have, it’s also because I’m capable of it. » Capable of this and much more, that’s for sure, judging by the determination he displays when asked what he has yet to achieve: « Getting to dance the role of Romeo was truly a big dream of mine. Now I’d love to do Siegfried in Swan Lake, which I think is a really wonderful role.”