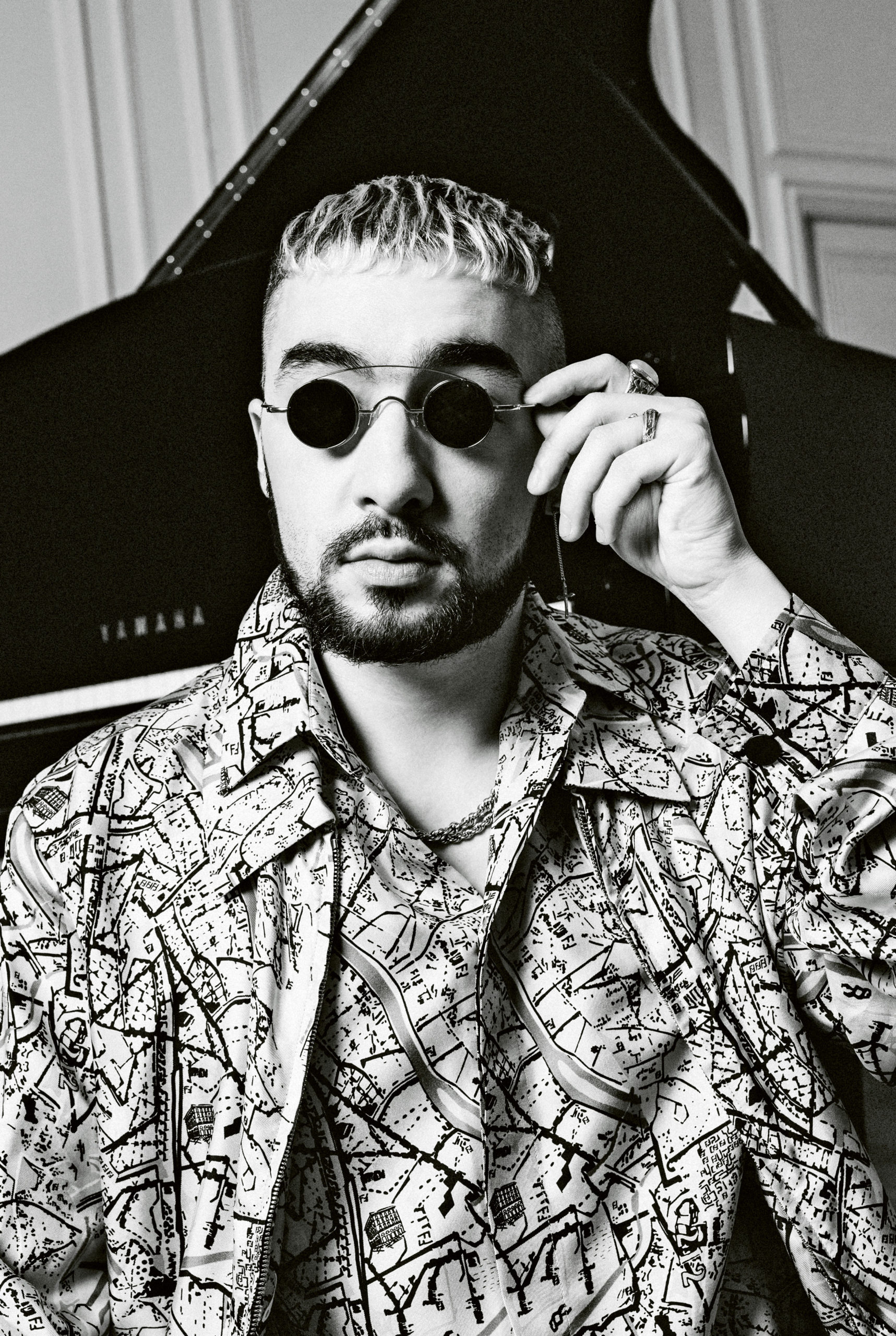

Sofiane Pamart is the new wonder of the pianosphere. Endowed with an absolute ear for music, his talent was first spotted by his parents when he was a child, playing the theme songs of mangas like Dragon Ball Z on his toy piano. After the Lille Conservatoire, he became a classical piano star, but chose to develop his personality and his repertoire by playing his own compositions exclusively, crowned with success in 2019 with his album Planet, revisited as Planet Gold last year. With a striking sense of style, he sports multicoloured coats, bucket hats, small round black glasses à la Leon, not to forget his grillz, a type of dental jewellery typical of the rap aesthetic. Rappers have been lining up to work with him: Sofiane composes for SCH, Vald, Rim’K, Hatik, Scylla and Médine, but also for pop and electro artists such as Bon Entendeur, NTO, Aloise Sauvage and Kimberose. We meet a young hyperactive gifted man, aiming for the position of “number one piano player in the world” and whose catchy melodies stand out at the crossroads between pop and classical music.

MIXTE. How did you get started in the world of classical music?

SOFIANE PAMART. It stems from the relationship I have with my parents. They are not musicians, but they have a crazy admiration for those who are. One day, my mother saw a documentary that said that the piano was the king of instruments – the fact that I call myself the Piano King comes from that! So I entered the Conservatoire at the age of 6. I had this dream of the institution, the top of the range, the great culture that the Conservatoire provides. But I was very rebellious and I was not a very academic person, unlike my mother. She was the one who taught me rigour. I already wanted to compose my own pieces, to play according to my mood… Fortunately, she stopped me. She had a strict authoritative presence. That’s what allowed me to acquire a technique.

M. You talk about method, but the trigger is still your talent, right?

S.P. Obviously, I had certain predispositions and that’s what made the difference. But I don’t like that kind of talk. We all have something special, it’s up to us to bring it out. As far as I’m concerned, I was lucky enough to discover the tailored timetables from secondary school onwards (the French education system has opened classes allowing you to divide your study time between the regular curriculum in the morning and the conservatoire in the afternoon, editor’s note). All throughout primary school, I followed my training in the traditional way and I have to say that combining school with music and solfeggio lessons was quite challenging at the time. The tailored timetables were a real plus.

M. Were you not put off by music theory?

S.P. It’s true that I didn’t like it. I’ve had teachers who didn’t understand me, and others who helped me to find an interest in it. There’s a mathematical side to it that can be cool if you look at it from that angle.

M. Finding an interest in this is amazing! Why don’t you share it with all the kids who don’t like it on YouTube, like Yvan Monka does with maths?

S.P. I think the key is to offer a course without focusing so much on theory. If you go through practical cases, the notion of solfeggio flows by itself. I did launch a company to pass on my pedagogy, but with all my current projects, it remained on stand-by.

M. Do you find the time to play the classical repertoire?

S.P. No, not at all. My time is so limited that every time I sit down at the piano it’s to compose new works. I haven’t had the time for that in five years. At the beginning, it was deliberate: I had decided to unlearn my fifteen years of training in three years. After that, I really felt free. I think I’ll come back to it, but much later. Besides, in my opinion, my music is classical music.

M. What do you think of the enormous repertoire of classical music, an almost compulsory end point for all young instrumentalists?

S.P. The problem is not the repertoire, which is magical, but what’s around it. It’s such a demanding practice that everyone adopts a posture and makes the whole thing feel stiff.. It’s a shame for such a high-level art form. You could approach it like the composers did when they created their works. But classical music has centuries of history, and performers have pushed the game to levels of excellence that lead audiences to compare existing versions. I’m lucky enough not to have this problem, because I play my own works. The great master with whom I got on best, Henri Barda, used to tell me: “You have to learn the works until you become the author”. He would transpose them in all directions to make sure that his fingers never guided his inspiration. I met him when I was 19 or 20 years old, when I was beginning to be introduced to the masters who prepare you for the biggest competitions. In every country, there are piano luminaries who take youngsters under their wing and allow them to thrive.